Three big ideas that will matter in 2026

And a call to action for robust demand-side energy markets

I’ve been doing a lot of my out-loud thinking on LinkedIn of late, and even more within my Claude Code environment, but as the year commences, and we continue to see extraordinary momentum towards real demand-side energy markets, it’s worth pulling a few related thoughts together here that might be counterintuitive to prevailing narratives, but important to internalize as we move forward.

1) Energy Efficiency is dead, but not for the reason you think it is

Last week, the Ad Hoc Group and Alliance to Save Energy published a report outlining how utilities could look to demand-side energy resources to solve their capacity challenges for siting new large loads. The most important takeaway from their report, aside from the obvious fact that demand-side energy resources are the cheapest, easiest and fastest to deploy in most parts of the country, is that energy efficiency isn’t actually the desired goal.

The purpose of deploying demand-side energy resources is not energy efficiency, but rather demand efficiency. In the era of cheap renewables and high load growth, reductions in energy consumption really only matter insofar as they coincide with peak demand.

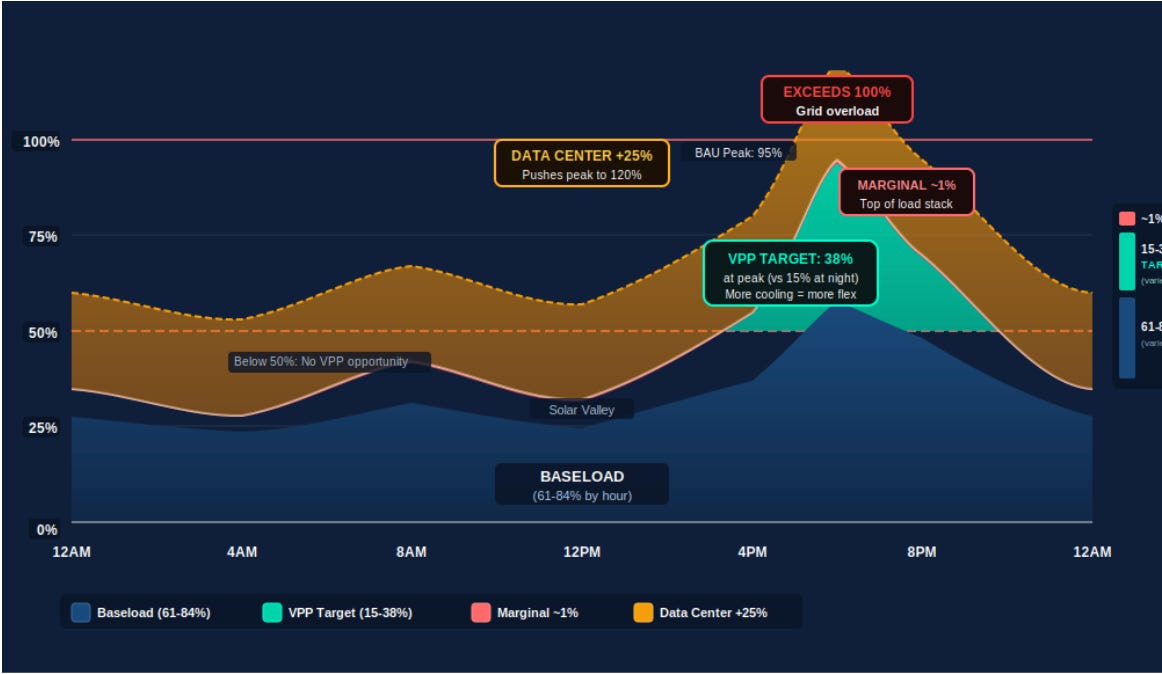

The implications for the energy efficiency world are profound. First and foremost, it means that all purported savings must be calculated using real world data, and done so on an hourly basis. Any sort of deemed measures, annual reporting, or adjustments based on what other people are “already” doing are simply a non-starter in the world of demand efficiency. Second, I expect to see energy efficiency programs generally start to be phased out. The image below (thanks Claude) highlights the problem. If the problem is grid capacity, we’re only talking about certain hours in a year that need to be tackled. Otherwise, adding load is a net positive for the grid (assuming that we’re also bringing more renewables online at the same time).

Energy “efficiency” assumes that all energy savings are created equal. But if your energy savings happen at noon and mine happen at 6pm, the grid is going to value mine a lot more.

Here’s how to think about demand efficiency. Imagine that for any given grid, there’s a finite amount of capacity to deliver the power we need (roughly analogous to a water pipe). There are a bunch of fixed costs that we have to pay to maintain the grid. We pay for these fixed costs through the electricity that’s delivered through the grid (think water flowing through a water pipe). The more electricity that we can send through the existing grid and charge people for on the other end, the lower the fixed costs per unit of electricity (we all pay a little bit less for infrastructure). However, if we have to build new capacity (get larger pipes for those peak days), our fixed costs go up and we have to pay more, even if the total amount of power that goes through the new wires is the same as what came before.

To put it in other terms, every additional kilowatt (kW) of capacity that we have to add ends up costing us money. Every additional kilowatt-hour (kWh) of electricity that we serve ends up saving us money. Energy efficiency might end up costing us money if it targets the wrong time of day! But energy efficiency when the grid is otherwise constrained saves us money, because it helps prevent the need to build new capacity.

Demand efficiency maximizes the number of kWh served by the grid while minimizing the amount of kW capacity that needs to be added to serve that kWh.

2) Demand Flexibility is valuable, but not for the reason that you think it is

Naming conventions are not a strong suit of our industry. While I will defend “PPAs for VPPs” until the bitter end, ask any random stranger to explain any of the acronyms that litter our industry white papers and you’ll be left with blank stares and baffled bemusement. Over the past five years or so, in an effort to not turn off the general public, our industry has coalesced around “demand flexibility” as the way to signal the value of demand-side energy resources. Do your laundry a little later, plug your car in earlier, activate your battery when called upon, etc. This “flexibility” is meant to resemble a giant coordinated grid-balancing machine. It’s not just a virtual power plant, it’s a virtual “peaker” plant, orchestrating thousands of different devices in an effort to optimize power flows!

This type of flexibility is cute until a 50 MW data center comes to town. Then it’s irrelevant. The problem at hand is not fiddling with marginal resources, but rather identifying the main drivers of peak energy use, and finding permanent, scalable solutions to reduce load during peaks without sacrificing customer comfort or further raising bills.

Another thing to consider is that depending on what part of the country you are in, your peak may be totally different than somewhere else in the country. These peaks are determined by power resources, historical energy use patterns, industrial clusters, and more. There is no one-size-fits-all solution.

But this is precisely why demand flexibility is an important, and valuable concept. Not because of the implied temporal shifting (though this can be helpful sometimes), but because you can mix and match demand-side energy resources depending on the particular peak challenges you face. Demand-side energy resources are diverse, by their very nature, and will most often be the most widely available precisely when local grid peaks are at their most severe.

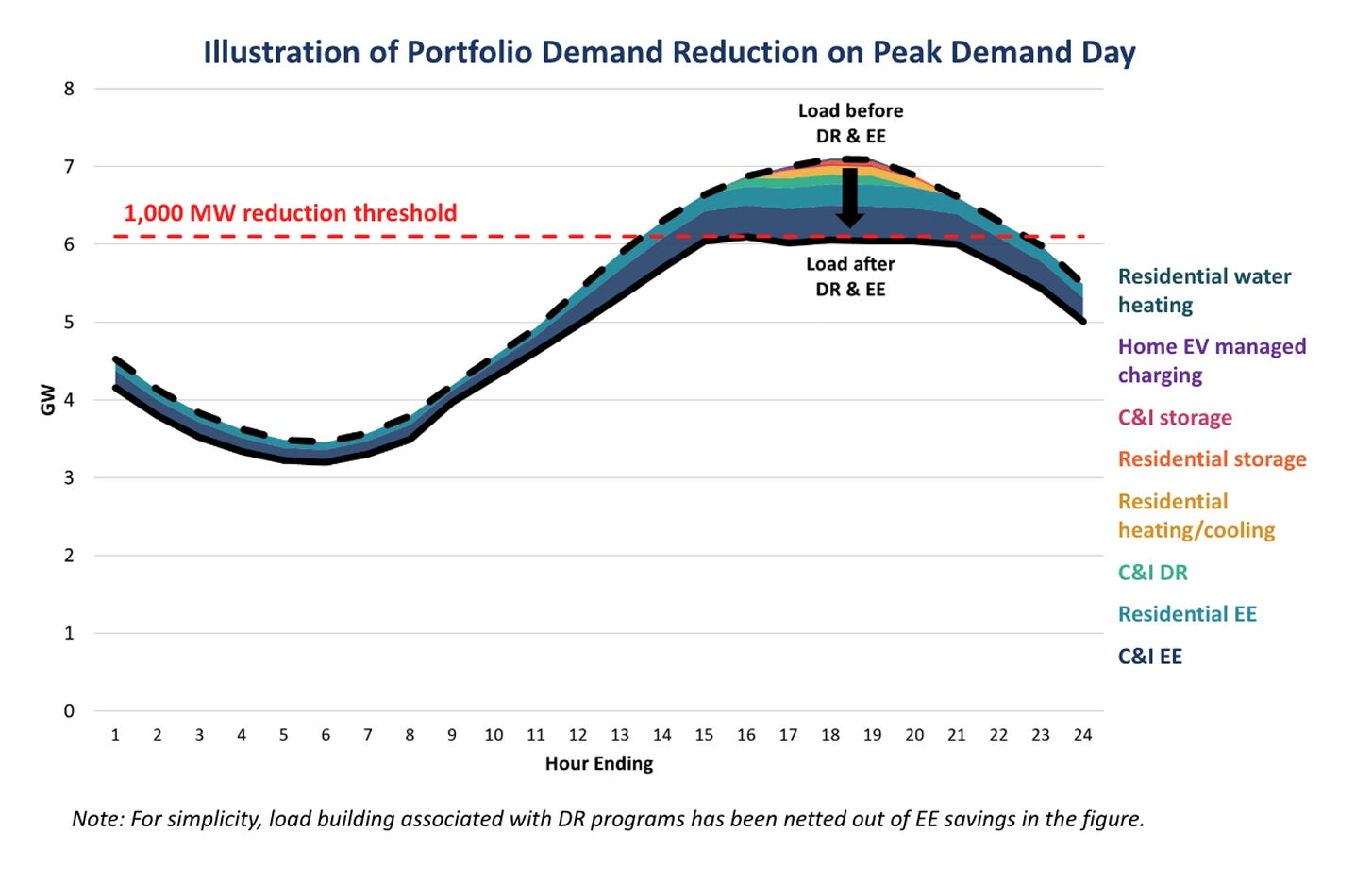

Rather than stipulating ahead of time what type of interventions are needed, a truly flexible demand-side energy resource strategy should focus on finding the peaks and sending the signal to the market for savings when the grid needs them most. Let the fact that there are diverse demand-side energy resources available be a feature, not a limitation of new demand-side energy markets. As the Ad Hoc group’s paper shows, a typical peak could be solved for with any combination of resources that are able to deliver during the required time frame.

3) Utility monopolies are bad, but not for the reason you think they are

Most Americans hate their utility. Over the past five years, favorability scores for utilities have dropped by nearly 50%. Three in four Americans believe that some sort of consumer choice for utility services would be preferable to a natural monopoly. Political candidates are riding a wave of dissatisfaction, stemming from rising rates and declining service, winning statewide elections and promising reforms. Very few economists or pundits stand up for utility monopoly rights and even those who do caveat their support with a litany of criticisms.

There are probably lots of valid points to be made, and its hard to blame people for being frustrated when their bills continue to go up, but the monopoly that we should worry more about isn’t the utility that’s selling you power; the monopoly we should pay attention to is the utility that is buying energy services from you.

The utility monopoly, in this case, is a monopsony - a single buyer rather than a single seller. They are buying energy services - everything from the solar on your roof to the managed EV charging in your garage to the energy efficiency in your attic. When they buy these services from you, they don’t have to spend money buying them elsewhere. Utilities use a tool called an Avoided Cost Calculator to determine how much they should spend on buying these services from you. You are, in essence, competing with a natural gas power plant for utility payments for your energy services.

If you choose not to accept a utility payment for your energy services, they will instead turn around and buy more or less the same service from a traditional power plant. There’s no real incentive for a utility to pay more for demand side energy resources, even if it means the grid gets cleaner, infrastructure costs go down, or consumer bills go down. You have basically zero bargaining leverage.

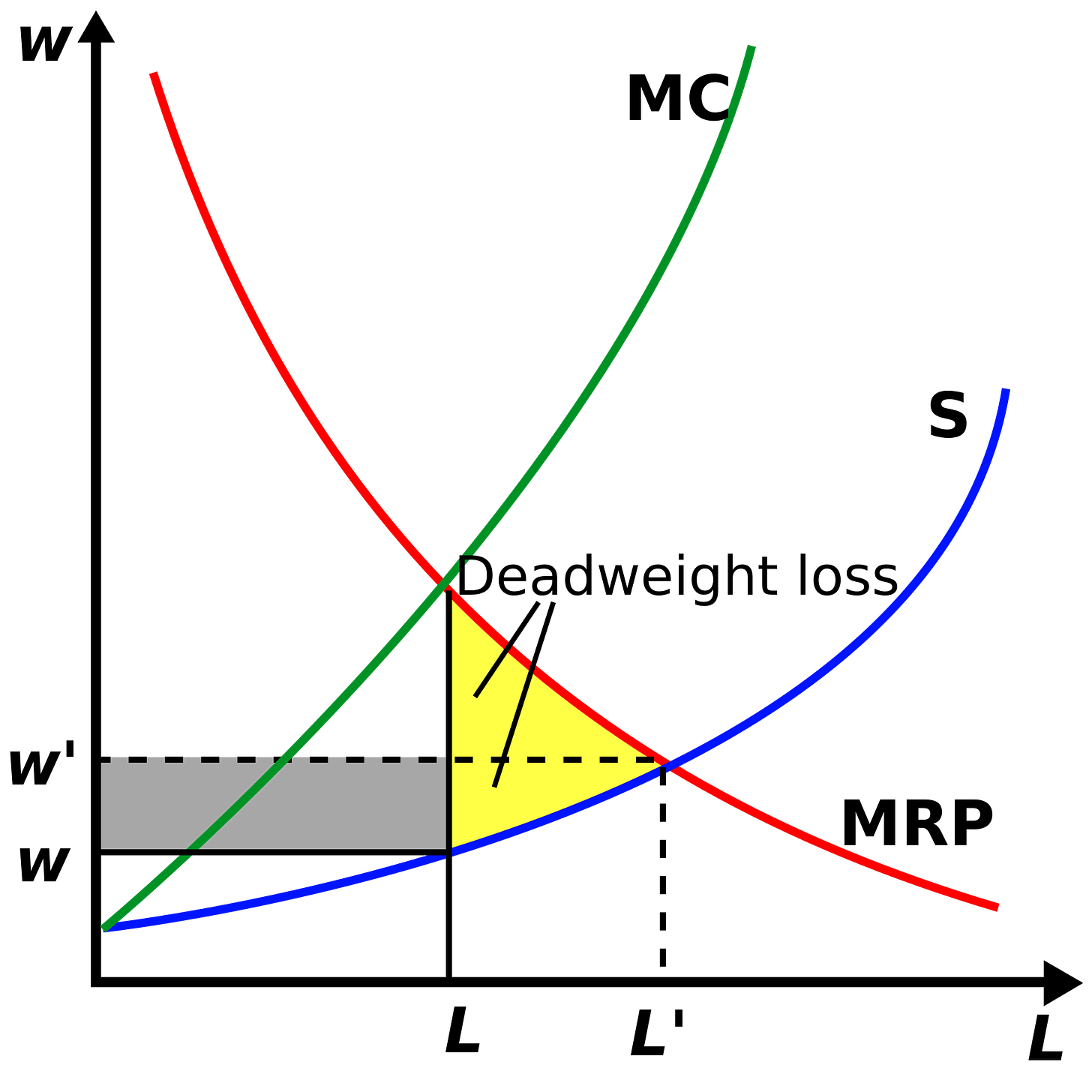

Imagine, though, what would happen if there were multiple buyers for your energy services! What if your rooftop solar or your battery or your attic insulation could be sold to another energy customer? If these energy customers competed for your services, the price that you could command would go up. I’m going to throw in an economics graph below to show how this works. Economists have figured out that competitive markets improve the bargaining power of sellers so that buyers can no longer capture monopoly rents from the market.

So what does this mean for demand-side energy markets? With all the drama over data centers needing to BYOC (Bring Your Own Capacity) and BYONCE (Bring Your Own New Clean Energy), perhaps it’s time to let them become buyers in the market for demand-side energy resources too. As our friends at the Ad Hoc Group pointed out (and before them Rewiring America and ACEEE), demand-side energy resources are the perfect complement to data centers. The main thing lacking is a market mechanism that allows them to efficiently procure this capacity and make a legitimate claim on it.

What we need are new open demand-side energy markets, embedded with measurement and verification, that support all types of distributed energy resources, and that come with systems of record that prevent double counting, that allow data centers and other large loads to procure these resources alongside traditional PPAs for generation. The utility still has a role to play here, of course. They need to specify the hours that matter and certify the savings calculations. They will have visibility into distribution networks that allow for better targeting of demand-side energy resources on a time and locational basis. Most importantly, utilities are custodians of economic growth and consumer welfare in our communities. Our utilities are essential participants in the well-being of our communities. They show up when the storms arrive and make sure that when the hottest and coldest days come that we all have the power we need to survive.

But it’s an all-hands-on-deck moment, where load growth threatens to overwhelm our capacity to manage it. If costs start to spiral, expect the political winds to blow in favor of complete restructuring of the utility ecosystem. If we don’t choose this moment to invest in our communities, keep costs in check, and minimize the new fossil fuel infrastructure we build, we should expect to pay the price for the next half-century or more.

You outdid yourself here, McGee. I love the framing of these 3 ideas!

The monopsony framing is super underrated here. I've been watching data centers negotiate power deals and its wild how little leverage DER providers have when theres only one buyer. The kW vs kWh distinction makes so much sence once you see it laid out like this, I remember analyzing some efficiency programs last year and realizing half the savings were happening at completely useless times.