What do you mean by "Marginal Emissions"?

Some thoughts on Consequential Emissions Accounting

Bitcoin Twitter is on fire with rumors of an impending exposé that calls out the carbon emissions from Bitcoin data centers across the United States. Somewhat on brand, many Bitcoin bro's are denying the validity of Scope 2 emissions accounting in the first place. "Bitcoin mining is perfectly clean, it's the electricity production that's dirty, but that's not our problem." Sigh.

The story does raise an interesting question about how to measure Bitcoin's impacts. The electricity use is undeniable. And carbon emissions from electricity production are real. While we may harbor some moral doubts about mining Bitcoin in the first place (an issue for another day, but regulating end uses seems dangerous to me), there are some important nuances in the way measurement happens that will have real public policy implications.

The article will apparently adopt a "consequentialist" approach to measuring the impacts of Bitcoin mining. This is a departure from the way that the GHG Protocols and the pending SEC rules will require public companies to report their emissions. More typical is an "attributional" approach, in which the emissions of the entire grid are apportioned to individual users according to their amount of electricity consumption.

A consequentialist approach makes a causal argument: "because" of your electricity use, certain emissions happen (or don't happen). The question being raised about Bitcoin mining is, of all of the emissions from the grid, which ones were caused by these data centers being turned on?

The presumption of the consequentialists is that since all existing electricity production is already spoken for by somebody else, any new production must be assigned to the power plant(s) that had to increase their generation to account for the new demand. These power plants operate at the margin, in the sense that when a grid operator decides which resources to include in its mix, it conducts a price auction and the last resource included in the mix sets the price (and earns the title of "marginal resource".

Unfortunately, nobody really knows what the marginal resource is going to be. The US EPA publishes a planning tool called AVERT that offers some regional marginal resource estimates (with the explicit caveat not to use the tool for any sort of accounting). The PJM grid operator publishes a marginal emissions number, but also heavily caveats it ("marginal units – and the marginal emissions rates based on them – cannot provide any prediction of the results of an action.") There are private companies that sell proprietary marginal emissions rates based on energy models. The best known is from the non-profit WattTime (and is apparently the one that Bitcoin story will be using). But you can get a marginal emissions number from Singularity Energy, Electricity Maps, Resurety, and probably others. They all produce somewhat dissimilar numbers from each other, but are all about equally "right" in their claim to the marginal emission "truth".

But these debates are theoretical (actually more like quasi-religious), and it seems more useful to actually look at what's happening on the grid. One state with a lot of Bitcoin mining growth in the past few years is New York. New York has one of the most ambitious clean energy goals in the country, and recently banned new Bitcoin mining facilities that source electricity directly from fossil fuel power plants.

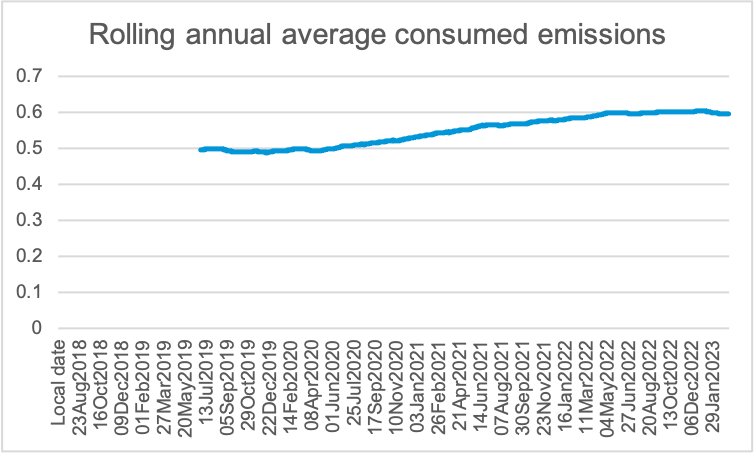

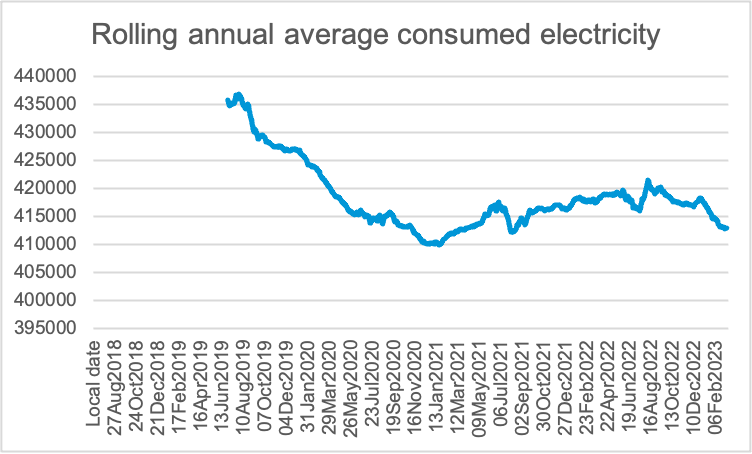

There's no question that New York's grid has become dirtier over the past five years. Data from the EIA shows that annualized carbon emissions per kWh have risen by 20% while total consumption has fallen by 5%.

If consumption is decreasing, and emissions are increasing, to whom do we assign the new emissions? If generally consumption is flat or declining, but there are new loads (in addition to Bitcoin mining, New York is rapidly electrifying heating and transportation), there must be old loads that are being retired (perhaps factories being shut down). Maybe it's the new solar and improved energy efficiency that's making the difference. It's not obvious how we can attribute the increase in emissions to any particular new load (or any load at all!).

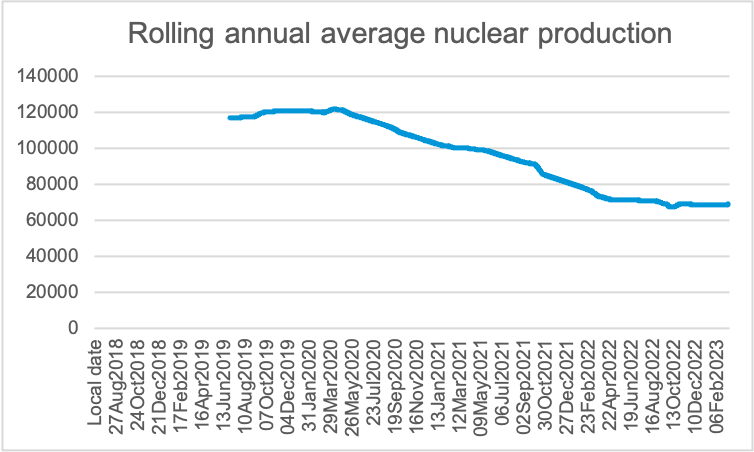

Another way to look at New York is to examine the changing composition of its grid fuel mix. One of the most "consequential" decisions in the past decade in New York was shuttering the Indian Point nuclear plant in Westchester County. Overnight, the emissions per kWh in New York started to rise as a result. While three upstate reactors remain operational in New York, the chart below shows the dramatic impact of closing Indian Point.

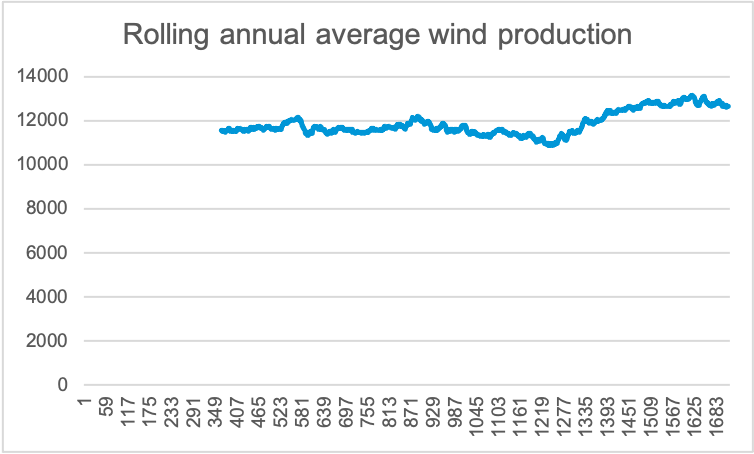

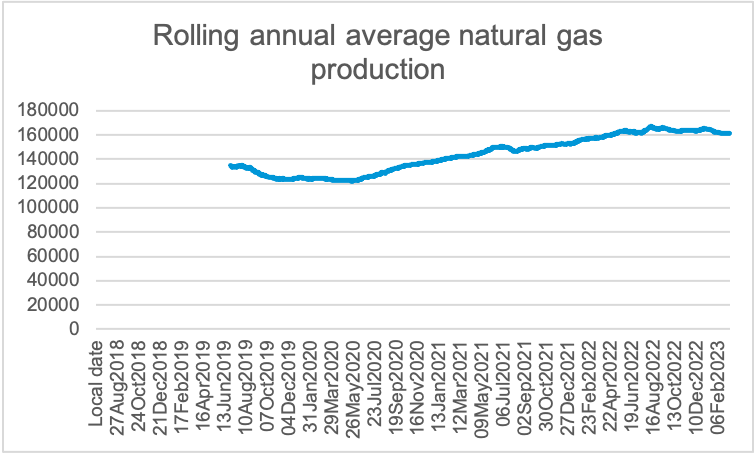

With this roughly 30% decrease in nuclear capacity, New York has been tasked with replacing the electricity with a combination of energy efficiency, distributed solar, wind, and natural gas. The fact that overall energy consumption has declined speaks to the success of distributed solar policies and energy efficiency. But new production has largely fallen onto the shoulders of natural gas and wind, with natural gas accounting for the largest share of new production over the past five years. Wind production has increased by a little less than 20% while natural gas production has increased by more than a third.

Stepping back, what seems to have happened in New York is a massive resorting of the fuels that power the grid. Nuclear has largely been replaced by natural gas and wind has stepped forward as a viable resource while distributed energy resources are helping to balance out new loads from electrification and even Bitcoin mining.

As we stop to think about what the emissions impacts are of certain end uses, it's useful to keep in mind that we are talking about large, complex systems that are hard to reduce to simple causal relationships. While it's easy to imagine in our minds that a decision to plug in our phone, charge our car, or mine for electronic gold will require a response from our power systems, however, like the proverbial butterfly flapping its wings, the consequences are far too diffuse to assign the energy load to a particular power plant. We all collectively benefit from an electricity grid. And we all bear some collective responsibility for the environmental impacts of the fuels that keep it operational.

The WRI's GHG Protocols have established a principle of fairness - you bear the responsibility for the portion of the grid's emissions that are proportional to your own consumption. You can take action by reducing consumption, adding solar panels to your roof, or using energy when there are more renewables on the grid. Or you can take action by pursuing a market-based pathway to net-zero in which you claim unique ownership of environmental attributes that help reduce grid carbon emissions. This principle of fairness is fundamentally threatened by the concept of "consequential emissions" where particularly dirty power plants are assigned to end users on a somewhat arbitrary basis. When I purchased my EV and added load to the grid, I didn't opt into the dirty power. But I understand that when I charge my car at night, when the grid is dirty, instead of the daytime, when there is ample solar on the grid, I am adding to the problem. We'll have to see what this article says about Bitcoin mining, but I worry that it will undermine good faith efforts to use emissions accounting as a guide to decarbonization.

A question on the New York emissions assessment- looks like the nuclear plant decommissioning may be the primary reason for increase in emissions. Maybe I misunderstood your point but that seems like direct correlation and emissions will be accordingly attributed to current loads.

Also - there was a roundtable conducted by Intel with Linux foundation on Blockchain. you may find the summary interesting. https://project.linuxfoundation.org/hubfs/LF%20Research/Intel%20Web3%20and%20Sustainability%20-%20Report.pdf?hsLang=en

During one breakout session, I found it interesting that bitcoin mining companies in the search for more sustainable power enable mechanisms for greening the infrastructure in Africa. Also, the article touches on carbon aware computing and how mining takes advantage of that.

I am not an advocate of bitcoin mining but thought these were interesting points to discuss.

I think you’re describing the challenge pretty well: attributional vs. consequential or average vs. marginal emissions. But if we step back, it seems that we should focus on approaches which serve to reduce emissions rather than increase them—full stop. When you look at the problem through that lens the value of the consequential or marginal approach makes more sense than any other. Clearly, it’s not perfect but the point should be that adding renewables to the highest emitting grids will have the greatest impact and that is worth doing. It’s not about hourly or monthly or annual accounting: to paraphrase James Carville, it’s the carbon, stupid!